Part 1: How Our Memory Works.

Longer chapters of my book, How to Grow Older without Growing Old, will be broken into shorter parts so they can be read more quickly. This is Part 1 of Chapter 6 of my book, How to Grow Older Without Growing Old. The Growing Older book can be purchased in its entirety at our website.

A simple way to explain how our memory works is that we have two distinct memory systems: short-term memory, also known as working memory, and long-term memory. Paying attention and properly hearing the information is usually enough to store it in our short-term memory, enabling us to easily repeat a name when we are first introduced. However, unless we make a conscious effort to transfer it to long-term storage, that memory quickly fades. That’s why I suggest repeating the name aloud during introductions, saying it silently to yourself several times, and writing it down for later review.

Now, assuming you store the information long-term, you may still have difficulty recalling it later. The extent of this difficulty depends on how effectively we memorized the information initially and how many cues we have created to retrieve it from our memory bank. The more you know about people you meet, the more cues you provide. Our minds operate through association. The more information you connect with people’s names, such as knowing their spouse’s name, where they work, their favorite food, hobbies, education, and so on, the more cues you create. Later, when trying to recall a person’s name, you can think about where you met, who introduced you, and a dozen other details linked to their name, and eventually, one of these facts (cues) will help you retrieve their name from long-term memory. Two things experienced together will become associated in our minds.

Focus, observe, and listen

According to Elaine Biech, author of ” Training for Dummies, ” about 70% of Western culture emphasizes visual learning. This means that while you should engage as many senses as possible when learning new material, the focus should be on the visual aspect. You play a significant role in the learning process, so don’t just sit back and absorb information. Your enthusiasm and physical activity also enhance the learning experience.

When you meet someone for the first time, ensure you truly observe their face, noting the various features. If you want to apply one of the memory expert’s techniques, attempt to create a connection between one of those features and the person’s name. This association technique will be illustrated later.

We tend to forget non-essentials and remember only the information we think about frequently or that carries emotional significance. According to Ernest Hartmann, a professor of psychiatry at Tufts University School of Medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, contemplating important thoughts activates our dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain area that aids memory. The more impressive, vivid, and emotional your thought is, the more likely you are to remember it.

The above fact will be used when I discuss the association method that can help you remember almost everything. The more you engage physically, mentally, and emotionally while memorizing, the easier it will be to recall the information later. A brain scan study reported in the journal Nature Neuroscience indicated that even making gestures while listening heightens activity in the brain’s memory center, activating other cells that wouldn’t normally be involved. It was discovered that even touching your ear or chin while learning a new phone number and then touching it again when trying to recall it will activate additional neural circuits that enhance your recall ability.

When you recall an event repeatedly, the initial recall tends to be the most accurate. It’s more akin to assembling a puzzle than to replaying a video. Memories are reconstructed each time they are accessed and are influenced by more recent experiences.

After the 9/11 attacks, psychologists surveyed several hundred subjects about their memories of that day. They later repeated the surveys with the same individuals one year later. By that time, 37% of the details had changed. By 2004, this figure had risen to 50%. The subjects were unaware that their memories had altered to such an extent; however, it is known that memories typically become less accurate the more they are recalled. This is where memory techniques come in, as they help to “cement” the memory in your brain.

Keeping your memory intact

As mentioned in chapter one, many people fear memory loss, particularly Alzheimer’s, more than they fear cancer, heart disease, and even death. Consequently, every time they can’t find their keys, leave a door unlocked, or forget someone’s name, they start to worry. This worry negatively affects the brain’s efficiency – especially memory.

Everyone experiences memory lapses, except for those who lie about it. In most cases, it is simply normal, age-related memory loss, not a sign of impending Alzheimer’s. While it can be inconvenient at times, you can compensate for it by using some of the memory techniques – and yes, gimmicks – that are described in this chapter.

In fact, many of these suggestions should help, even if you are in the early stages of dementia of any kind. Just like crossword puzzles, reading, continuing education, and any other activity that engages your brain, these suggestions can help compensate for, delay, or in some cases (as illustrated in the “Nun Study” described later), even mask some of the symptoms of dementia altogether.

I used to facilitate memory training workshops over 30 years ago and still rely heavily on these same techniques to remember people, access codes, passwords, tasks, and events. Even then, I find myself forgetting certain things at times. On a few occasions, I have temporarily forgotten the name of my best friend or a relative. However, I don’t worry about it. Anxiety and stress are the enemies of memory. If you have ever had to prepare and then deliver a speech, toast, or eulogy, you know exactly what I mean.

I’ll tell you right away that the most effective memory system is writing things down. The pen is mightier than the mind when it comes to recall. Not only can you refer to the written word (or digital format, if that’s your preference), but the act of writing things down also aids in remembering them.

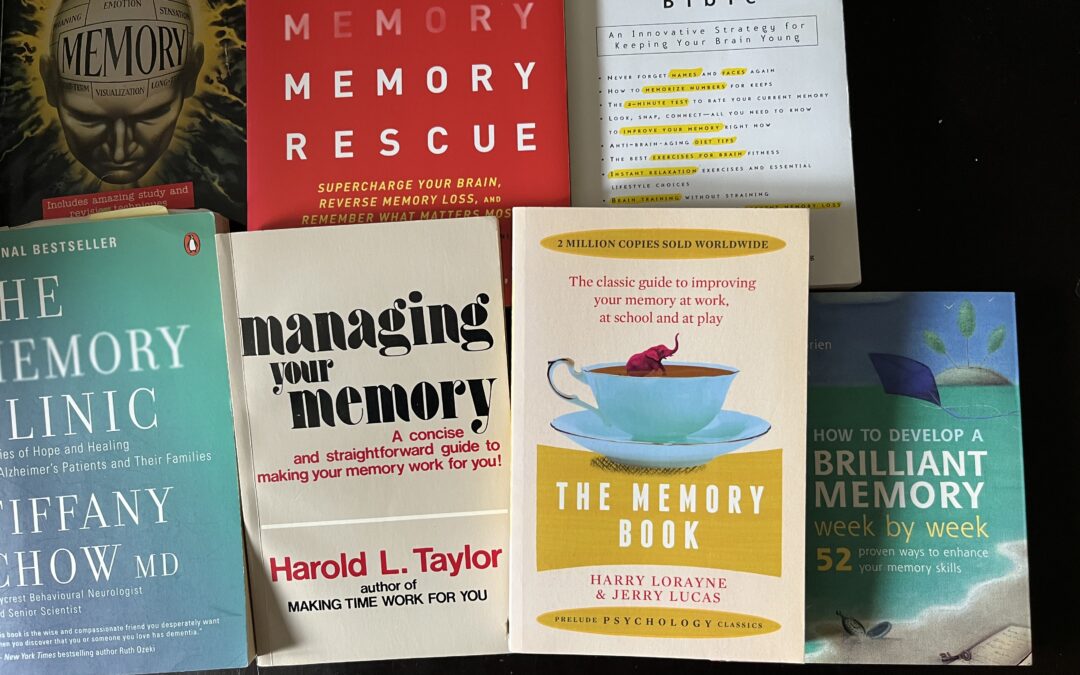

I never thought that memory techniques would be useful in cases of dementia, even though I have relied on them myself all these years to compensate for age-related memory loss. However, last week I picked up a copy of Gary Small’s book, The Alzheimer’s Prevention Program: Keep Your Brain Healthy for the Rest of Your Life.

Dr. Gary Small, along with his wife Gigi Vorgan, has authored several books on the brain, and in this book, they assert that memory training can slow age-related decline and even enhance the cognitive performance of individuals with mild cognitive impairment. They suggest that seniors “may be able to stave off some Alzheimer’s symptoms for years by learning and practicing memory enhancement techniques.”

The book supports those statements with research. Perhaps I was correct in predicting the significance and popularity of time management when I selected it as the topic for my workshops; however, it pales in comparison to brain health – a term that wasn’t even used back in the 70s when I began my career as a speaker and trainer.

I have dusted off my old memory training notes. (Yes, I am a packrat when it comes to training materials.) Surprisingly, I can still recall most of those one hundred 4-digit numbers that I memorized over 35 years ago. There’s a trick or technique involved, of course, but it’s one of the techniques that I have been using all these years to remember my social insurance number, PINs, ‘ to-do” lists, and other information.

When I speak to senior groups, I risk a bit of embarrassment by including memory training. Who cares if I forget a name or two – or a dozen or more? If I can help stave off dementia, it’s well worth it.

What truly aids in remembering anything is having interest in and paying attention to the name or information you wish to recall, followed by frequent repetition of the information.

If you think you will never meet a person again or never use a piece of information in the future, you are already conveying to your brain that you’re not interested. For example, I suggest that you may not be interested in how remembrance occurs in our brains, as described in the next brief section, because it does not aid in your actual recall. Attention, interest, and repetition are the three essentials for remembering. We refer to this as the A I R formula – Attention, Interest, Repetition. If practiced consistently and sincerely, these three elements alone will significantly boost your recall.

Types of Remembering.

Memory consists of several components, and not all of them decline with age. Semantic memory, which is the ability to express oneself using vocabulary, typically does not decline with age. Likewise, procedural memory, the skill necessary to perform routine tasks that you have carried out for most of your life, such as preparing breakfast, getting dressed, and making phone calls, remains intact.

Age does influence episodic memory, which is the ability to remember recent events, source memory, where you recall where you heard a joke or read about certain facts, prospective memory, the ability to remember to perform specific tasks in the future, and working memory, which is the capacity to temporarily store information until it is needed, such as looking up a phone number and then dialing it immediately, or adding a series of numbers in your mind.

Although these latter ones may all decline with age, as previously mentioned, they don’t necessarily have to if you utilize memory techniques or continuously exercise your brain. The more you use your brain, the more cognitively fit it will become, and practicing memory techniques is one effective approach to achieve that.

Not all memory loss is equal, nor serious. Age-related memory loss is normal, but it is not inevitable. Normal memory loss, unlike MCI (mild cognitive impairment), involves forgetting information that isn’t particularly important to you – such as the name of a stranger you briefly met at a party last night or where you left your keys This inconvenient and time-consuming memory loss can often be avoided by simply paying attention and concentrating on what you hear and where you put things. As mentioned, writing things down also helps solidify memories. The brain does not transfer anything to long-term memory that doesn’t seem important to you.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is more significant and may indicate that you’re not keeping your brain in peak condition. According to Dr. Anthony Komaroff, a physician and professor at Harvard Medical School, there are two types of MRI: amnesic and non-amnesic. Individuals with non-amnesic MCI face difficulties with cognitive functions beyond memory, such as finding the right words to express themselves or changing a printer cartridge. To enhance or prevent any cognitive impairment, you should maintain a healthy diet, stay socially active, and remain both physically and mentally fit, along with following the other suggestions outlined in Chapter 1.

Scientists have shown that exercise staves off both age-related and disease-related declines in brain function. The March/April 2012 issue of Scientific American Mind reported on a study indicating that exercise achieves this by producing new mitochondria, tiny structures inside cells that supply the body with energy. J. Mark Davis, a physiologist at the University of South Carolina who was involved in the study, stated, “The evidence is accumulating rapidly that exercise keeps the brain younger.”

MCI increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and a study conducted by Baycrest Health Service’s Rotman Research Institute indicates that anxiety further elevates this risk. For MCI patients experiencing mild, moderate, or severe anxiety, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s increases by 33%, 78%, and 135% respectively. Dr. Linda Mah, a psychiatrist in Toronto and the study’s lead author, suggests that to alleviate anxiety, individuals should ensure they get sufficient sleep and exercise, and refrain from worrying about the future.

Worrying about the future undoubtedly involves concerns that you may already have MCI and could be on the path to Alzheimer’s. Thinking this way might actually bring it about. The next time you catch yourself gazing into the refrigerator, wondering what you are doing there, just laugh it off. There have been times when I’ve even forgotten my brother’s name, struggled to remember where I parked my car, and left the house wearing my slippers.

Today, more than ever, we find ourselves in an environment that fosters forgetfulness and inattention. In this fast-paced digital age, eye contact has been substituted with iPhones, face-to-face interactions have been replaced by Facebook, and conversations have given way to texting. Eating healthy food, exercising both your body and mind, building your social network, and laughing often can be beneficial. It may also help to slow down, focus more on the present than the future, and manage your usage of technology and the Internet.

Recent Comments